In the rich tapestry of Indian classical music, the term Gharana holds profound cultural, pedagogical, and aesthetic significance. Derived from the Hindi word ‘घराना’ meaning ‘house’ or ‘family’, in the context of music, a Gharana refers to a distinctive school or lineage of musical thought and performance, often established by an extraordinarily gifted artist. Over generations, these traditions have evolved through the oral transmission of style, technique, and philosophy, forming unique identities within the greater framework of Hindustani classical music.

Hindustani music itself is a composite art form, comprised of three pillars: vocal music (gīt), instrumental music (vādy), and dance (nṛtya). Each of these has developed individual streams of performance, some of which were later consolidated into Gharanas by visionary artists and their disciples. A Gharana thus emerges when a maestro, through his singular genius and interpretation, forges a unique style of rendition — be it vocal, instrumental, or dance — which is then passed down to disciples who adopt and refine this style under his guidance.

Table of Contents

Individuality in Expression: The Seed of a Gharana

Every artist, shaped by personal temperament, musical education, and socio-cultural environment, performs music in a manner that reflects their unique sensibility. With age and experience, this individuality becomes more pronounced, influencing the nuances of performance. When such an artist possesses exceptional talent and insight, their distinctive method of rendition often takes root and flourishes into a full-fledged musical tradition — a Gharana.

This tradition is strengthened through guru-śiṣya paramparā, the revered teacher-disciple lineage, wherein the disciple absorbs not only the musical technique but also the artistic temperament of the guru. Over time, as disciples and their disciples continue this legacy, the specific stylistic characteristics of the Gharana become well recognised and respected within the musical community.

The Meaning of the Term ‘Gharana’

Linguistically, ‘Gharana’ implies noble descent or an illustrious family lineage. Musically, it denotes a school of thought characterised by a distinctive and original mode of expression developed by a particular artist or family, which earns recognition and widespread acceptance. Often, a Gharana is named after either the pioneering artist who established the tradition or the place where the style originated and matured.

Historically, Gharanas are believed to have taken shape in a more formalised manner during the 14th century, although earlier musical lineages such as those of the Kalāvants and Qawwāls had already established some musical conventions. With the passage of time, these Gharanas became emblematic of specific stylistic identities in performance, each with its own aesthetic, technical and pedagogical philosophy.

The Guru-Shishya Tradition: Training Within a Gharana

One of the most essential features of a Gharana is its unique method of training. This education is often imparted through a rigorous and immersive residential system wherein the disciple lives with and serves the guru, undergoing years of intense musical discipline and spiritual refinement. The disciples were expected to submit fully to the guidance of the guru, often assisting in daily chores and routines, and dedicating themselves entirely to the study of music.

This aśrama-like system of musical learning was not merely about acquiring skills, but about internalising an entire worldview and aesthetic rooted in the Gharana. There was no room for personal innovation during the learning phase; creative liberty was only encouraged after the disciple had mastered the foundational idiom of the tradition.

Upon completing their training, disciples were granted permission by the guru to perform publicly. Those who demonstrated exceptional calibre often became gurus themselves, continuing the lineage by training the next generation and thereby expanding the reach of the Gharana.

How a Gharana is Formed and Sustained

Typically, it is believed that a Gharana is formed through at least three generations of musical practice and preservation. It begins with a prodigious guru, passes through his immediate disciples, and gains stature when those disciples train further generations who continue to uphold and enrich the tradition. Each Gharana, thus, becomes a living continuum — dynamic yet rooted, evolving yet grounded in its founding vision.

Over time, a Gharana becomes distinguished by:

A particular style of ornamentation and phrasing

Characteristic approaches to rāga development

Specific tāla preferences and rhythmic interpretations

Repertoire choices, such as compositions or genres emphasised

Methodologies of voice culture, tonal aesthetics, or bodily expression (in dance)

Categories of Gharanas: Vocal, Instrumental, and Dance

In the Indian subcontinent, Gharanas have traditionally been classified based on the nature of their performance focus. These include:

Vocal Gharanas (Gāyak Gharanas)

These Gharanas have been founded by accomplished vocalists whose distinct vocal style led to the establishment of an identifiable school. Vocal gharanas are further categorised into four sub-genres:Dhrupad Gharanas

Khayal Gharanas

Thumri Gharanas

Tappa Gharanas

Instrumental Gharanas (Bādak Gharanas)

These Gharanas arose from the virtuosity and stylistic innovation of renowned instrumentalists. They are primarily classified into:Tābadak Gharanas (Percussion-based traditions like Tabla, Pakhawaj)

Ānaddhabādak Gharanas (String and wind instruments like Sitar, Sarod, Shehnai)

Dance Gharanas (Nartak Gharanas)

Dance Gharanas are based on unique movement vocabularies, rhythmic structures, and storytelling techniques established by iconic dancers. Particularly in Kathak, the most prominent classical dance form of North India, the main Gharanas include:Lucknow Gharana

Jaipur Gharana

Benares (Varanasi) Gharana

In Bharatanatyam, a South Indian classical dance form, the key Gharanas (also referred to as Banis) include:

Tanjore Bani

Thiruvallur Bani

Pandanallur Bani

Pillai Bani

Gwalior Gharana – The Cradle of Khayal

1. Historical Origins

The Gwalior Gharana is widely acknowledged as the oldest and most influential school of Khayal singing in Hindustani classical music. Its roots trace back to the 16th–17th centuries in the princely state of Gwalior (now in Madhya Pradesh), where the genre of Khayal itself underwent significant development. Although the precise founding guru is a matter of some scholarly debate, tradition often cites Nathan Pir Bakhsh as an early pioneer, followed by Naththan Khan and Farrukh Hussain in subsequent generations.

Under the patronage of the Scindia rulers of Gwalior, the gharana flourished. It laid down a systematic approach to Khayal that balanced structure and improvisation, thereby becoming the benchmark for countless other gharanas that emerged later.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Gwalior Gharana is renowned for several defining features that together create its distinctive sound:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Bandish-Centricity | Emphasis on the bandish (fixed composition) as the core around which improvisation revolves. |

| Clarity of Swarās | Precise intonation and clear articulation of each note, ensuring the purity of the melodic line. |

| Balancing Laya and Bhava | Skillful interplay of rhythm (laya) and emotion (bhava), without sacrificing either. |

| Bol–Alap | Use of lyrical syllables in the alap (slow, unmetered introduction) to deepen raga exploration. |

| Taan Patterns | Well‑structured and rhythmically precise ‘taans’—both short and long—often in even (‘sapat’) and uneven (‘mishra’) groupings. |

| Layakari | Nuanced rhythmic play with the tabla, featuring cross‑rhythms and syncopations. |

| Straightforward Aesthetics | A relatively unembellished style, favouring natural melodic flow over excessive ornamentation. |

These elements combine to produce performances that are both elegant and disciplined, showcasing a seamless integration of composition and improvisation.

3. Pedagogical Tradition : Guru–Shishya Paramparā:

The Gwalior Gharana’s teaching methodology, upheld through guru–shishya paramparā, places great emphasis on:

Memorisation of Bandishes

Disciples commit to memory a wide repertoire of bandishes in various ragas, often in multiple rhythmic cycles (tālas).Voice Culture and Aesthetics

Fundamental voice‑training exercises focus on breath control, tonal clarity, and smooth transitions between notes (meend).Progressive Learning

Instruction begins with simple compositions in slower tempos, gradually advancing to faster renditions and more complex taans and rhythmic patterns.Holistic Immersion

In traditional settings, students lived alongside their guru, absorbing performance etiquette, repertoire, and the philosophical underpinnings of the style.

4. Notable Exponents

Over three centuries, the Gwalior Gharana has produced numerous legendary vocalists whose artistry has both preserved and evolved the tradition:

Ustad Haddu Khan (1850–1910) and Ustad Hassu Khan (1850–1875)

Brothers credited with refining the gharana’s khayal style and popularising it in northern India.Pandit Vishnu Digambar Paluskar (1872–1931)

Renowned for founding the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya music schools and codifying the gharana’s teaching for broader dissemination.Pandit Krishnarao Shankar Pandit (1893–1989)

A prolific teacher and performer whose disciples continue to represent the Gwalior tradition internationally.Pandit Bhimsen Joshi (1922–2011)

Although primarily associated with Kirana Gharana, his early training was in Gwalior style; he integrated its robust bandish orientation into his own expressive singing.Pandit Ulhas Kashalkar (b. 1955)

A modern-day maestro respected for his authenticity, teaching, and preservation of the Gwalior idiom.

5. Influence and Legacy

The Gwalior Gharana’s bandish-based approach set a template for Khayal singing that subsequent gharanas either adopted or reacted against. Its hallmarks—clarity, structured improvisation, and rhythmic precision—can be observed in many other major Khayal schools, including Agra, Jaipur-Atrauli, Patiala, and Bhatkhande-Marwar gharanas.

Today, Gwalior-trained vocalists and teachers continue to:

Champion Traditional Repertoire: Ensuring rare bandishes in old ragas are not lost to time.

Adapt to Contemporary Contexts: Presenting classical recitals on global stages, collaborating across genres, and using modern recording technology.

Teach New Generations: Via conservatories, online platforms, and residencies, thus extending the gharana’s reach worldwide.

The Gwalior Gharana remains a cornerstone of Hindustani classical music, revered for its timeless balance of form and freedom. Its centuries-old ethos—rooted in respect for tradition yet open to subtle innovation—ensures that the gharana continues to inspire both practitioners and listeners.

Agra Gharana – The Majestic Dhrupad Legacy in Khayal

1. Historical Origins

The Agra Gharana claims a venerable lineage that traces its roots to the Dhrupad–Dhamar tradition, the oldest extant school of North Indian classical singing. Historically centred in the city of Agra, this gharana was shaped by the Nauharbani and Khandarbani branches of Dhrupad vocalism. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, leading exponents such as Haji Sujan Khan and Ghagge Nazir Khan began to adapt the robust, meditative Dhrupad style to the more fluid and improvisatory Khayal genre. Thus, Agra Gharana emerged as a formidable synthesis of Dhrupad’s solemnity and Khayal’s expressive freedom.

Under the patronage of the Mughal courts and later the princely rulers of Agra, the gharana prospered. Its practitioners preserved the nom-tom alap (vocalises on ‘nom’ and ‘tom’ syllables) and layakari (complex rhythmic interplay) characteristic of Dhrupad, while embracing the bandish‑centred structure of Khayal.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Agra Gharana is distinguished by the following hallmark features:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Dhrupad Roots | Retention of nom‑tom alap, long ‘aakaar’ phrases, and the grave tonal quality of Dhrupad. |

| Robust Voice Projection | Emphasis on full, open-throated singing; a commanding timbre capable of carrying intricate lines in large spaces. |

| Bol‑Baant & Bol‑Taan | Ornamentation and improvisation using the syllables of the bandish itself, generating rhythmic excitement. |

| Layakari | Virtuosic cross‑rhythmic play, often deploying tihai and parhant (cadential patterns) to dramatic effect. |

| Nom‑Tom Alap | Slow, unmetered opening in nom and tom syllables that explores the raga’s fundamental contours. |

| Khali‑Jor‑Jhala | A progression from unaccompanied nom-tom to a measured jor section and an exciting jhala finale in faster tempo. |

| Bandish Emphasis | Careful exposition of the composition’s lyrics and melody, ensuring clarity of poetic content alongside musicality. |

Together, these elements yield performances of solemn grandeur, fusing meditative depth with rhythmic vigour.

3. Pedagogical Tradition

Guru–Shishya Methodology

Teaching within the Agra Gharana follows the time‑honoured guru–shishya paramparā, featuring:

Immersive Apprenticeship

Disciples live with their guru, assisting in daily duties and internalising every nuance of the style through constant exposure.Sequential Training

Instruction begins with the nom‑tom alap, then progresses to bandishes in vilambit (slow), madhya (medium), and drut (fast) tempos.Voice Conditioning

Rigorous exercises develop the capacity for sustained, resonant singing essential to Dhrupad‑influenced delivery.Rhythmic Mastery

Special emphasis on mastering complex talas, cross‑rhythms, and improvisational cadences which are integral to the gharana’s aesthetic.

4. Eminent Exponents

Over the years, the Agra Gharana has produced towering figures whose artistry has defined its reputation:

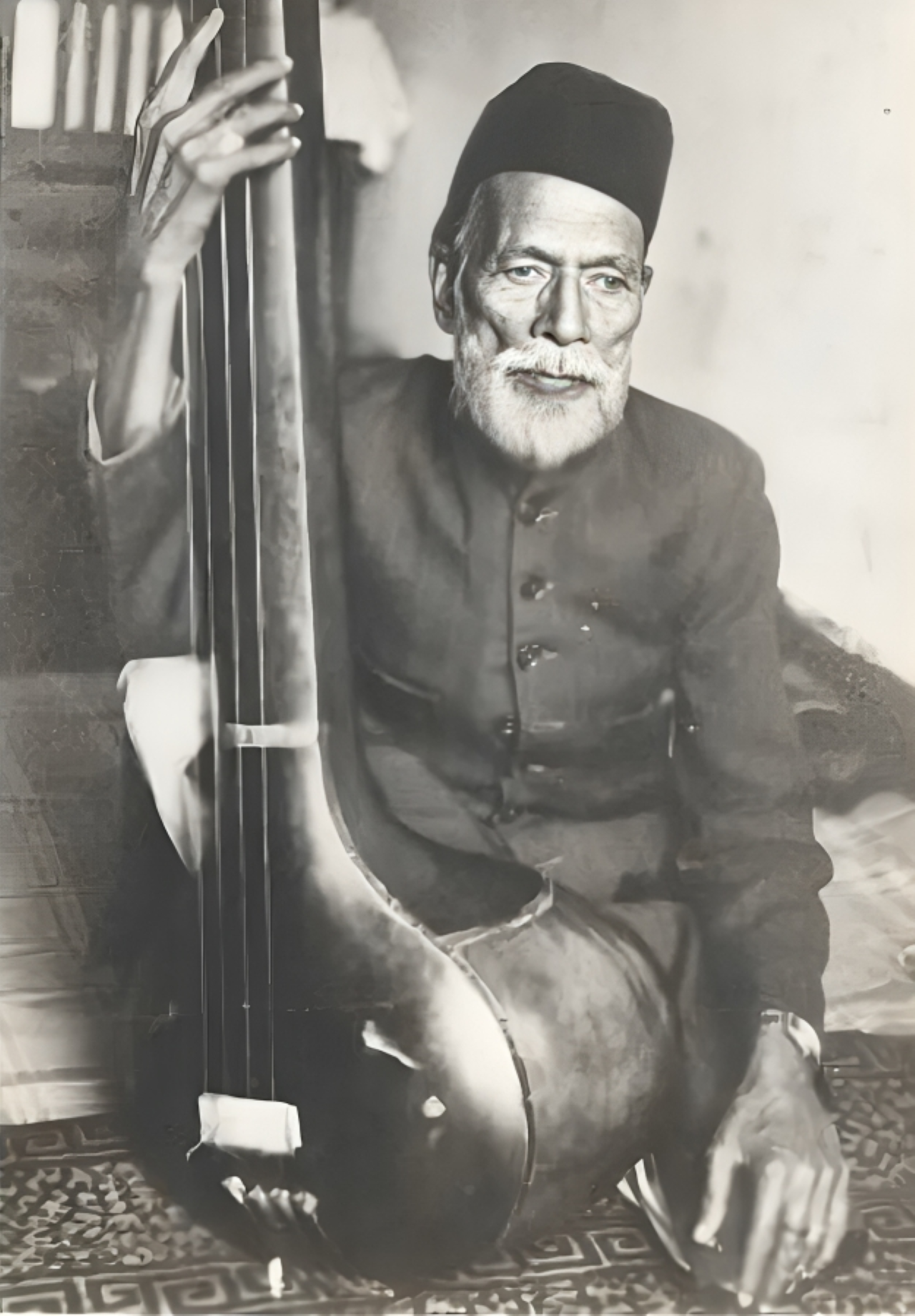

Ustad Ghagge Nazir Khan (c. 1850–1920)

Celebrated for codifying the fusion of Dhrupad and Khayal techniques.Ustad Haji Sujan Khan

A master whose nom‑tom alap became a signature of the gharana’s meditative opening.Ustad Faiyaz Khan “Aftab-e-Mausiqui” (1882–1950)

Widely revered as one of the twentieth century’s greatest vocalists, known for his erudition and emotive depth.Ustad Vilayat Hussain Khan (1895–1962)

Legendary teacher and composer of numerous bandishes still sung today.Ustad Ata Hussain Khan (1885–1958)

Renowned for his eloquent layakari and persuasive tonal quality.Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan (b. 1957)

A foremost contemporary exponent, celebrated for faithful renditions and pedagogical work.

5. Influence and Legacy

The Agra Gharana’s powerful synthesis of Dhrupad solemnity with Khayal flexibility has profoundly influenced Hindustani vocal music:

Its nom‑tom alap has inspired generations of Khayal singers to incorporate more extended, meditative openings.

The gharana’s bol‑baant techniques inform rhythmic improvisation across many schools.

Its emphasis on a robust voice and dynamic stage presence has shaped performance practice in large concert halls and festivals.

Through institutions and private teaching, Agra-trained artistes continue to transmit its rich repertoire and technical mastery worldwide.

The Agra Gharana stands as a testament to the enduring vitality of India’s musical heritage. Its unique marriage of the ancient Dhrupad tradition with the later Khayal form has bequeathed to listeners and practitioners a style of profound solemnity, rhythmic ingenuity, and expressive depth—one that continues to command reverence across the globe.

Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana – The Harmonious Blend of Melody and Rhythm

1. Historical Origins

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana is one of the most illustrious schools of Hindustani classical music, with a rich history deeply rooted in the blending of intricate melodic phrases with rhythmic precision. This gharana traces its origins to the Atrauli region of Rajasthan, where Ustad Shankar Pandit and his disciples began shaping its distinctive style during the 18th century. By the 19th century, under the leadership of Ustad Alladiya Khan, this gharana gained widespread recognition and became synonymous with melodic beauty and rhythmic sophistication.

The gharana’s development was largely influenced by the Dhrupad and Khayal forms, with Ustad Alladiya Khan at the helm of its popularisation, particularly in Jaipur, where he was patronised by the royal family. The gharana thus came to be known as Jaipur-Atrauli, a fusion of its geographic origins and the artistic contributions of its key masters.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana is recognised for its synthesis of intricate melodic and rhythmic elements. The primary features of this gharana include:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Melodic Ornamentation | Use of meend (glide between notes) and gamak (oscillation) to create rich, expressive phrases that define the raga. |

| Bandish Structure | Preference for both vilambit (slow) and drut (fast) tempo bandishes, with a balanced structure that allows for improvisation. |

| Vocal Timbre | Smooth, clear vocal tone with emphasis on blending dynamics and resonance throughout the range of the voice. |

| Layakari | Rhythmic virtuosity with complex tala cycles, including tihai, parhant, and other rhythmic cadences. |

| Bada Khayal | Preference for expansive bada khayal (elaborate compositions), where the mood is deeply explored in improvisation. |

| Pehla Khayal | The phela khayal (the first composition) is often rendered with an intense alap and detailed exploration of the raga. |

| Tuning | The gharana uses slightly modified tunings, making the performance sound more resonant and melodious. |

This style is famous for its broad melodic range and rhythmic complexity, which is a hallmark of the Jaipur-Atrauli tradition.

3. Pedagogical Tradition

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana follows a strict guru-shishya paramparā, or teacher-student tradition, where the student’s commitment to learning is of utmost importance. Here are the key elements of their training methodology:

Emphasis on Alap

A considerable amount of time is dedicated to learning the alap (unmetered, meditative introduction) in various ragas. Students are taught to begin slowly and develop the raga with extended phrases that bring out its mood and essence.Mastery of Bandish

Students learn to sing bandishes in both vilambit and drut tempos. The emphasis is on intonational accuracy and the use of subtle ornaments such as meend and gamak.Layakari and Tihai

The gharana places significant importance on rhythmic intricacies. Students learn to perform tihai (repetitions of a rhythmic phrase) and parhant (rhythmic patterns) to develop their rhythmic skills. The student’s ability to combine melody and rhythm fluidly is considered a mark of mastery.Focus on Voice Culture

Just like the Agra Gharana, the Jaipur-Atrauli tradition stresses voice culture exercises to develop a resonant and controlled tone, ensuring clarity in both high and low registers.

4. Eminent Exponents

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana boasts a line of legendary exponents who have contributed significantly to its growth and propagation:

Ustad Alladiya Khan (1855–1952)

The founder of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana, Ustad Alladiya Khan is regarded as one of the greatest vocalists of the 20th century. His innovative approach to Khayal performance, especially his emphasis on both melody and rhythm, remains influential to this day.Ustad Jitendra Abhisheki (1929–1998)

A prominent figure in the gharana, Ustad Abhisheki is known for his exquisite renditions of Khayal and Dhrupad, along with his deep understanding of ragas and talas.Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (1872–1937)

A pioneer of the gharana, Ustad Abdul Karim Khan is credited with transforming the vocal style by incorporating more fluid and improvisatory techniques into Khayal. His legacy continues to inspire musicians worldwide.Ustad Rashid Khan (b. 1966)

A contemporary exponent of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana, Ustad Rashid Khan is known for his mastery over the bandish and his ability to weave intricate layakari into his performances.

5. Influence and Legacy

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana has had a profound impact on both Hindustani classical music and the larger tradition of Indian vocal performance. Here are some of the ways it has shaped the music world:

The gharana’s balanced synthesis of melody and rhythm has become a model for future generations of classical vocalists, with a focus on aesthetic refinement and technical mastery.

The emphasis on alap and bandish has influenced many other gharanas, contributing to the diversity of vocal styles across the subcontinent.

The gharana’s layakari and rhythmic intricacies have made it a sought-after school for students interested in virtuosity and improvisation.

Through its disciple system, the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana has ensured the continuity of its style, with prominent vocalists from the gharana training the next generation of musicians, thereby preserving its legacy.

The Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana is a prime example of the fusion of melody and rhythm in Hindustani classical music. With its rich tonal quality, rhythmic complexity, and innovative bandish structures, it has secured its place as one of the most influential gharanas in Indian music history. Its legacy continues to thrive through the efforts of its stalwart practitioners and their students, who carry forward its ideals of musical excellence and artistic expression.

Kirana Gharana – The Meditative Voice of Hindustani Classical Music

1. Historical Origins

The Kirana Gharana is one of the most celebrated and influential gharanas in Hindustani classical music, renowned for its deeply melodic and introspective style. Its name is derived from Kairana, a small town in present-day Uttar Pradesh, which was the birthplace of Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (1872–1937), the principal architect of the gharana’s modern form.

While the early roots of the Kirana tradition can be traced back to the Dhrupad and Khayal styles, it was Ustad Abdul Karim Khan who shaped it into a distinctive school of Khayal singing, incorporating aesthetic lyricism, long, slow alaps, and a strong focus on intonation (swara shuddhi).

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Kirana Gharana is particularly known for its emotive depth, slow unfolding of ragas, and devotional essence. The stylistic hallmarks are summarised below:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Swara-focused Approach | Great emphasis on the purity and emotional quality of each note (swara), often explored with extended meend and aakar. |

| Slow Alap Development | Ragascapes are unfolded very gradually through vilambit alap, often lingering on a single note to extract its full emotive power. |

| Minimal Layakari | Unlike Jaipur or Agra Gharanas, Kirana avoids complex rhythmic improvisations, choosing instead to focus on the melodic journey. |

| Voice as Instrument | The voice is used almost like a string instrument, with long glides, soft attacks, and a restrained vibrato (andolan). |

| Use of Taan | Taan patterns in Kirana are soft, flowing, and melodically connected, rather than being fast or flashy. |

| Bandish Preference | Typically selects poetic, lyrical bandishes, often with devotional or romantic themes (bhakti or shringara rasa). |

The essence of Kirana Gharana lies in its spiritual undertone, where each note is treated as a living entity, and the raga is revealed with a meditative grace.

3. Pedagogical Tradition

Training in the Kirana Gharana involves a long and patient journey, often beginning with hours of swara sadhana (note practice) to cultivate both technical perfection and emotional resonance. Its teaching methods include:

Swara Sadhana

Students begin by practising sargam, aakar, and meend across the scale. The teacher ensures each note is struck perfectly, without rushing to faster improvisations.Raga Alap Practice

Learners are taught to slowly unfold a raga through vilambit alap, often focusing on one note per session. This intense focus builds emotional depth and intonational clarity.Voice Cultivation

The Kirana approach emphasises voice culture, often using long, sustained aakar to develop breath control, tone, and resonance. This method helps create the trademark calm, introspective vocal quality.Emotional Interpretation

Beyond technical skill, students are encouraged to imbue emotion into their singing, aligning with the devotional and romantic essence of Kirana bandishes.Minimalist Layakari

Unlike some other gharanas, students are not required to focus heavily on rhythmic variations. The emphasis lies in melody, bhava (emotion), and laya (tempo) rather than complex tala work.

4. Eminent Exponents

The Kirana Gharana has given rise to some of the most beloved and respected figures in Indian classical music, including:

Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (1872–1937)

Revered as the founder of the Kirana Gharana’s modern tradition, he brought a sublime emotionality and refined melodic style to Hindustani music. His renditions of ragas like Yaman and Todi remain benchmarks of vocal beauty.Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan (1871–1949)

A cousin and fellow pioneer of the gharana, his approach was slower and more meditative than even Abdul Karim Khan’s, with profound focus on long, drawn-out alap.Pandit Bhimsen Joshi (1922–2011)

A towering figure in Indian classical music, Pandit Bhimsen brought a powerful, emotive intensity to the Kirana tradition, blending technical brilliance with devotional fervour. His energetic taans and passionate delivery made him a household name.Gangubai Hangal (1913–2009)

A disciple of Sawai Gandharva (Bhimsen Joshi’s guru), Gangubai’s voice had a deep, earthy tone that gave new expression to Kirana’s emotional core. She made significant contributions to expanding the gharana’s female representation.Prabha Atre (b. 1932)

Known for her academic insight and innovative compositions, Prabha Atre enriched the gharana with new bandishes while maintaining its purity. Her renditions balance scholarship and soul.

5. Influence and Legacy

The Kirana Gharana has profoundly shaped modern Khayal performance. Its focus on melody over rhythm, and its deeply emotive rendering of ragas, have made it one of the most widely followed gharanas among students and connoisseurs alike.

The gharana’s emphasis on swara purity has influenced musicians across gharanas, creating a renewed focus on melodic accuracy and tone.

Its exponents have built bridges between classical music and the wider public, especially through radio, recordings, and festivals.

With its deeply introspective style, the Kirana Gharana has become a natural choice for artists seeking spiritual expression through music.

Today, its legacy continues through a large number of disciples and institutions around the world who uphold the gharana’s teachings and values.

The Kirana Gharana offers a spiritual sanctuary within the vibrant landscape of Hindustani classical music. Its melodic purity, devotional essence, and introspective mood make it one of the most cherished and influential traditions of Khayal singing. Through the legacy of maestros like Abdul Karim Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, and Gangubai Hangal, this gharana continues to inspire musicians and listeners in search of musical and emotional depth.

Gwalior Gharana – The Classical Pillar of Khayal Tradition

1. Historical Foundations

The Gwalior Gharana holds the distinction of being the oldest Khayal gharana in Hindustani classical music. It laid the very foundation upon which modern Khayal singing has evolved. Rooted in the princely state of Gwalior in Madhya Pradesh, this gharana traces its heritage back to the early 19th century, with origins often linked to Nathan Pir Bakhsh and more prominently his grandsons, Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan.

The patronage of the Scindia rulers of Gwalior, who were great connoisseurs of music, provided a nurturing environment for the gharana’s flourishing. The Gwalior Gharana’s teachings and compositions became the standard framework for Khayal, influencing almost every other gharana that emerged in its wake.

2. Stylistic Features

The style of the Gwalior Gharana is marked by clarity, precision, and balance. It focuses on compositional strength, rhythmic structure, and clear enunciation, offering a perfect blend of melodic expression and rhythmic command.

| Element | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Bandish-centric Style | Great emphasis on the bandish (composition), which serves as the backbone of performance, elaborated with improvisations that never overshadow the main theme. |

| Tans and Bol-baant | Use of powerful and structured taans, and bol-baant (manipulation of text in rhythm), with keen attention to syllabic clarity. |

| Rhythmic Precision | A hallmark of the gharana is its mastery of layakari (rhythmic play), where the artist explores intricate patterns within the tala framework. |

| Voice Projection | Strong, open-throated voice with bold presentation, enabling clarity even in complex passages. |

| Raga Development | Ragas are presented in a structured and balanced form, avoiding over-indulgence in alap or taan, with clear vistar (elaboration) in both slow and fast tempos. |

The Gwalior style is didactic and disciplined, making it ideal for pedagogical foundations in classical music training.

3. Pedagogical Approach

As the earliest formal system of Khayal instruction, the Gwalior Gharana has long served as a training ground for vocalists who later went on to define other gharanas. Its teaching method is systematic and rigorous:

Training in Basic Ragas and Bandishes

Students begin with well-known bandishes in common ragas such as Yaman, Bhairav, and Bhupali. The focus remains on clarity, swara shuddhi (note purity), and tala accuracy.Introduction to Layakari

Learners are introduced early to basic and advanced rhythmic variations, using techniques like dugun, tigun, chaugun (double, triple, quadruple time) within the bandish.Practice of Taan and Bol-taan

Students develop command over taans in different speeds, as well as bol-taans where the lyrical content is rhythmically manipulated for artistic expression.Raga Lakshan Geet

A unique contribution of the Gwalior Gharana is the use of Lakshan Geet – didactic compositions that describe the structure and characteristics of each raga in verse form.Strong Oral Tradition

The tradition emphasises guru-shishya parampara (oral transmission), with students learning through close imitation and repetition under the guidance of their guru.

4. Prominent Exponents

The Gwalior Gharana boasts an illustrious lineage of stalwarts who set the standard for Khayal singing. Some of the most distinguished figures include:

Haddu Khan & Hassu Khan (19th Century)

The legendary brothers are credited with shaping the gharana’s distinct identity, especially its emphasis on structured taans and bol-baant. They trained numerous disciples and systematised the Khayal format.Balkrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar (1849–1926)

A student of Haddu Khan, he was instrumental in spreading the Gwalior style in Maharashtra and training the next generation of vocalists.Vishnu Digambar Paluskar (1872–1931)

One of the most revered reformers, he was responsible for popularising classical music among the masses and founded the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in 1901.Krishnarao Shankar Pandit (1893–1989)

A torchbearer of the gharana into the 20th century, his performances and teaching helped preserve the classical purity of the Gwalior tradition.D. V. Paluskar (1921–1955)

Son of Vishnu Digambar, his brief yet brilliant career remains a shining example of classical artistry, remembered for his pure tone and refined delivery.

5. Legacy and Modern Influence

Though sometimes considered less ornate than other gharanas, the Gwalior Gharana’s influence is vast and enduring. Its codified methods, balanced style, and pedagogical strength make it the bedrock of Hindustani vocal training.

Gharanas such as Agra, Jaipur, and even Kirana have been indirectly influenced by Gwalior’s emphasis on structure and clarity.

Its bandishes are used widely in music institutions across India, forming the core repertoire of many syllabuses.

With a strong institutional presence, especially in Gandharva Mahavidyalayas, the gharana continues to thrive in both academic and performance spaces.

The Gwalior Gharana is the architectural cornerstone of Khayal music. With its emphasis on compositional strength, clarity of rendition, and disciplined pedagogy, it has nurtured a legacy that continues to shape classical vocalism in India. It remains the ideal entry point for students embarking on a journey through the world of Hindustani classical music.

Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana – Graceful Eloquence Rooted in Tradition

1. Historical Lineage and Origins

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana is intrinsically linked to the Gwalior Gharana, often seen as a stylistic offshoot. It emerged during the mid-19th century, under the royal patronage of Nawab Rampur, who provided fertile ground for the arts to blossom.

The gharana takes its name from Rampur (in present-day Uttar Pradesh) and Sahaswan, the native town of its founding family. The founder, Ustad Inayat Hussain Khan (1849–1919), was a disciple and son-in-law of Haddu Khan of Gwalior, and brought with him a deep mastery of the Gwalior style.

However, over time, the gharana developed its own distinct personality, marked by elegance, sophistication, and musical restraint.

2. Stylistic Features

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana is celebrated for its measured grace, intellectual clarity, and well-structured raga exposition. While retaining the compositional strength of the Gwalior style, it introduces a gentler, more fluid expression, with emphasis on vocal quality and lyrical sensitivity.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Bandish-Centric Approach | Strong reliance on bandishes, often those inherited or adapted from the Gwalior repertoire, with intricate but tasteful improvisation. |

| Voice Culture | Emphasis on clear enunciation, open-throated tone, and delicate modulation, allowing for expressive, resonant singing. |

| Layakari and Taans | Skilled but subtle use of layakari, and well-crafted taans that are typically slow, meend-laden, and executed with effortless grace. |

| Bol-Alap and Bol-Taans | Rich use of lyric-based elaboration, ensuring that the poetry of the bandish remains central to the aesthetic experience. |

| Structure over Ornament | While taans and sargams are present, they are deployed judiciously, always in service of the raga’s emotional essence. |

The gharana values restraint over flamboyance, appealing to connoisseurs who seek depth, clarity, and refinement in performance.

3. Pedagogical Methodology

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana is noted for its structured training, which focuses on gradual immersion into the deeper aspects of raga and tala. The teaching unfolds through the following steps:

Basic Ragas and Bandishes

Students begin with a core curriculum of ragas in slow and medium tempo bandishes, developing clarity in pitch and diction.Voice Development

Training involves extensive practice in voice culture, including akar, meend, and gamak, ensuring smooth, well-rounded vocal output.Application of Ornamentation

Ornamentation such as murki, khatka, and zamzama are taught in context, and students are trained to avoid excessive embellishment.Introduction to Layakari and Taans

Rhythmic understanding is developed through slow, methodical exploration of taans, often with attention to their lyrical alignment.Attention to Bhava (Emotion)

Expression is not merely musical but also literary and emotive, and learners are encouraged to explore the emotional world of the bandish text.

4. Eminent Exponents

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana has produced a distinguished line of vocalists, many of whom have played pivotal roles in shaping Hindustani classical music in the 20th century and beyond.

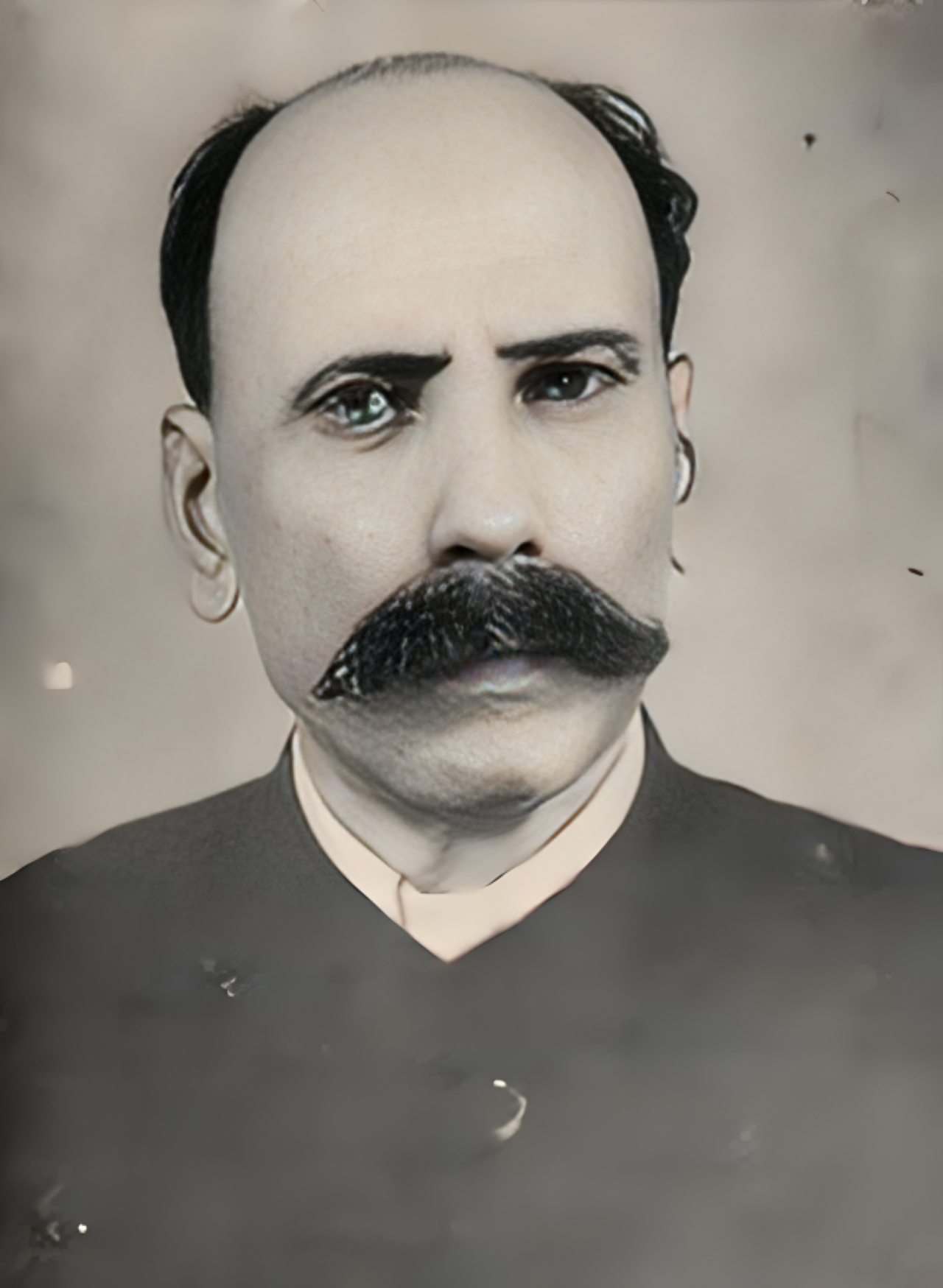

Ustad Inayat Hussain Khan (1849–1919)

Founder of the gharana, he blended the rigour of Gwalior with his own lyrical style, setting a precedent for future generations.Ustad Mushtaq Hussain Khan (1878–1964)

The first Hindustani classical vocalist to receive the Padma Bhushan, he was a revered teacher at the Sangeet Natak Akademi and mentor to many.Pandit Shrikrishna Ratanjankar (1900–1974)

Scholar, composer, and performer, he was known for his original bandishes and was a respected academician who trained several leading musicians.Pandit Ghulam Mustafa Khan (1931–2021)

A celebrated figure in both classical and light classical circles, he trained many film and stage singers while remaining a pillar of classical discipline.Ustad Rashid Khan (b. 1968)

A modern maestro, known for his soulful taans, impeccable sur, and capacity to effortlessly bridge classical and semi-classical genres. He has brought the Rampur-Sahaswan style to global audiences.

5. Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana represents the synthesis of tradition and refinement. Its teachings continue to resonate in contemporary performance spaces, institutions, and among music lovers who appreciate poise, depth, and lyricism.

It remains deeply embedded in academia, with many exponents serving as gurus in top music universities.

The gharana’s balance of technique and aesthetics makes it particularly suitable for students seeking intellectual engagement with music.

It is respected for maintaining a pure classical identity, even while embracing cross-genre collaborations in recent decades.

The Rampur-Sahaswan Gharana carries forward the majestic lineage of Gwalior, yet stands tall on its own merits — offering an aesthetic that is simultaneously intellectual, lyrical, and emotionally resonant. It represents a quieter, more introspective path into the heart of Hindustani classical music.

Patiala Gharana – The Dazzling Jewel of Vocal Virtuosity

1. Origins and Historical Background

The Patiala Gharana emerged in the late 19th century under the patronage of the royal court of Patiala in present-day Punjab, India. It was founded by Ustad Ali Baksh Khan (1850–1920) and Ustad Fateh Ali Khan (1855–1901), both originally trained in the Delhi Gharana, and later influenced by elements from Gwalior, Kirana, and even Punjab folk traditions.

These two pioneering brothers earned the title ‘Ali-Fattu’, becoming legendary for their dynamic performances and technical prowess. What followed was the birth of a gharana known for its rhythmic brilliance, sweeping taans, and dramatic flair.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Patiala style is instantly recognisable for its vibrancy, exuberant ornamentation, and virtuosic taankari. It blends classical rigour with popular appeal, making it both respected among purists and beloved by wider audiences.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Spectacular Taans | High-speed, powerful, and gamak-rich taans, often executed with showmanship, energy, and rhythmic variations. |

| Bol Baant and Layakari | Advanced and inventive use of bol-baant (rhythmic division of lyrics) and layakari, enhancing drama and excitement in performance. |

| Use of Thumri and Tappa | Integration of semi-classical forms such as thumri, tappa, and ghazal, lending emotional colour and lyricism to the singing. |

| Open Throat Singing | Strong, resonant voice production with an open-throated, full-bodied tone, suitable for both grandeur and expressiveness. |

| Aesthetic Extravagance | Deliberate emphasis on ornamentation and dazzle, often characterised as flamboyant yet controlled. |

The gharana is often associated with a kind of musical charisma—emotional, immediate, and electrifying.

3. Teaching Tradition and Approach

The pedagogy of the Patiala Gharana is as robust as it is exhilarating, focusing on developing power, control, and flair in the student.

Voice Projection and Strength

Training includes exercises to build vocal stamina, especially for fast-paced taans and intricate sargams.Mastery over Taankari

A significant portion of training is devoted to varied taans—akar, bol-taan, gamak-taan, sargam-taan—encouraging spontaneity and innovation.Tala and Rhythm

Emphasis is placed on intricate layakari, with students learning to navigate and play with complex rhythm cycles.Thumri and Semi-Classical

Students are encouraged to explore lighter genres, cultivating expression, bhava (emotional content), and ornamentation skills.Emotional Connection

While technique is crucial, teachers also stress the importance of performance charisma, connecting deeply with both raga and audience.

4. Illustrious Exponents

The Patiala Gharana has given Indian classical music some of its most iconic and beloved figures, many of whom left indelible marks on both classical and popular music traditions.

Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan (1902–1968)

Widely regarded as one of the greatest vocalists in Hindustani music, he combined patiala flamboyance with kirana subtlety and brought a divine lyricism to his music. His thumris are still considered benchmarks of beauty and finesse.Ustad Barkat Ali Khan (1905–1963)

A younger brother of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, he was a master of ghazal, thumri, and dadra, bringing unmatched pathos and elegance to lighter genres.Ustad Amanat Ali Khan and Ustad Fateh Ali Khan (Pakistan)

This legendary duo carried the Patiala flag in Pakistan, known for their tandem performances and emotive style.Ustad Hamid Ali Khan and Shafqat Amanat Ali

Modern torchbearers in Pakistan, they blend classical depth with contemporary aesthetics, especially in crossover and Sufi music genres.Pandit Ajoy Chakrabarty

An eminent Indian classical vocalist who, while trained in multiple gharanas, prominently showcases Patiala elements, particularly in his spirited taankari and melodic improvisations.

5. Contemporary Relevance and Legacy

The Patiala Gharana continues to thrive due to its broad appeal and adaptability. Its vibrancy suits both concert hall and popular music, and many of its exponents have crossed over into film, Sufi, and fusion music, reaching new audiences globally.

Blends tradition and entertainment, making it ideal for modern concert dynamics.

Inspires young students who seek a powerful, dramatic approach to classical vocalism.

Encourages personal expression and innovation, especially in rhythm and taans.

The gharana, therefore, enjoys a rare dual identity—as a bastion of classical tradition and as a lively, ever-evolving school of expression.

The Patiala Gharana stands tall as a celebration of vocal prowess, a vibrant tradition where melody dances with rhythm, and emotional depth meets sheer vocal athleticism. It is a gharana that has captivated generations and continues to set hearts racing with its exuberant artistry.

Bhendi Bazaar Gharana – The Urban Sophistication of Tonal Precision

1. Origins and Historical Background

The Bhendi Bazaar Gharana traces its roots to the late 19th century in the Bhendi Bazaar area of Bombay (now Mumbai)—a culturally rich, urban quarter inhabited by a diverse population. It was founded by Ustad Chhajju Khan, originally trained in the Delhi Gharana, and later enriched by the contributions of his disciples and descendants.

This gharana evolved in an environment steeped in linguistic, religious, and musical pluralism, absorbing elements from Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and local Marathi musical practices. It reflects the cosmopolitan ethos of Mumbai and exhibits urban refinement, mathematical elegance, and a highly cerebral approach to raga development.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Bhendi Bazaar Gharana is distinctively known for its precise intonation, microtonal purity, and systematic voice culture techniques. Its strength lies not in grandeur or flamboyance but in depth, intellect, and tonal clarity.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Swar-Lagav (Note Placement) | Emphasis on perfect intonation of notes (swaras), including detailed work on shruti-based microtones, creating a refined tonal palette. |

| Systematic Voice Training | Highly developed system of voice culture, including breath control, vowel modulation, and projection tailored for clarity and resonance. |

| Use of Meend and Gamak | Subtle and delicate use of meend (glides) and gamak (oscillations), always maintaining tonal integrity. |

| Medium to Slow Tempos | Preference for vilambit and madhya laya over drut, allowing exploration of tonal contours and emotional textures. |

| Composition-Focused Style | High priority is given to the bandish (composition), which serves as the framework for raga exposition. |

The approach is analytical, introspective, and less ornamental, attracting connoisseurs who value nuance and depth over flamboyant display.

3. Teaching Tradition and Methodology

The Bhendi Bazaar Gharana is known for its disciplined, scientific training methodology, often involving precise vocal exercises and raga drills.

Swar Sadhana

Students are trained in exact pitch rendering, often using the harmonium or tanpura to align and internalise subtle note positions.Breath Control and Tone Shaping

Breathing techniques and tonal control exercises are crucial to achieving a stable, smooth voice with rich timbre.Analytical Raga Study

Every raga is deconstructed with technical insight, studying swara hierarchy, phraseology, and emotional potential.Compositional Fidelity

Importance is placed on memorising and interpreting traditional bandishes, before proceeding to improvisation.Soft yet Strong Voice

The voice is developed to be flexible and responsive, rather than forceful, allowing for detailed expressive control.

4. Renowned Exponents

Though the gharana is not as widely known as others, it has produced some of the most respected musicians in Hindustani classical music, many of whom were revered for their intellectual rigour and tonal mastery.

Ustad Aman Ali Khan (1888–1953)

Regarded as the most prominent figure of the gharana, he was famed for his command over pitch and sensitive raga delineation.Ustad Abdul Rehman Khan

A vital figure in popularising the style, known for his dedication to tone refinement and subtlety.Pandit T.D. Janorikar

A major torchbearer in post-independence India, he helped preserve and propagate the gharana’s rich repertoire and teaching system.Dr. Prabha Atre

Though a student of Kirana Gharana, she studied with Ustad Sureshbabu Mane, who was deeply influenced by Bhendi Bazaar style, incorporating its nuanced voice culture and swar-lagav into her own style.

5. Legacy and Contemporary Significance

In an age where speed and spectacle often dominate, the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana continues to represent a quiet intellectualism in Indian classical music. Its contribution to voice training and note perfection has found relevance even in modern vocal pedagogy.

Influences various modern vocalists who borrow from its scientific vocal techniques.

Appeals to music students interested in precision, depth, and tonal aesthetics.

Often studied by vocal trainers and fusion artists looking to build a clean and expressive voice.

Although it has fewer direct exponents today, the gharana’s teachings survive in subtle currents, deeply embedded in the training practices of other traditions and conservatories.

The Bhendi Bazaar Gharana is a gem of tonal purity, standing apart for its calm sophistication, emotional subtlety, and scientific rigour. It reminds us that in Indian classical music, there is as much power in restraint and refinement as in grandeur and display.

Banaras Gharana (Vocal) – The Sacred Sound of the Ghats

1. Origins and Historical Background

The Banaras Gharana, also known as the Varanasi Gharana, traces its spiritual and musical roots to the holy city of Varanasi (Banaras)—the cultural and religious epicentre of India for millennia. While vocal music in Banaras dates back centuries, the gharana formally emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, growing from a rich confluence of classical, semi-classical, and devotional traditions.

Rather than being a product of royal patronage, the Banaras Gharana thrived under the temple and community traditions, evolving in ghats, ashrams, and satsangs, nourished by a strong Bhakti (devotional) undercurrent.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Banaras Gharana is known for its unique blend of classical precision with devotional expressiveness, embracing forms like khayal, thumri, dadra, chaiti, kajri, and tappa. Its hallmark is a soulful and emotive style, deeply resonant with the spiritual ethos of the region.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Emotive Expressiveness | Heavy emphasis on bhava (emotion) and rasa (aesthetic mood), often invoking deep devotion or romantic longing. |

| Semi-Classical Richness | Thumri, dadra, and kajri are not treated as light forms but with sophisticated raga treatment and ornamentation. |

| Layakari and Lyrical Flow | Intricate rhythmic play is fused with smooth, flowing melodies, creating a beautiful tension and release. |

| Bol-Baant and Bol-Banao | Both structure-based (baant) and expressive/improvised (banao) approaches to compositions are employed. |

| Use of Folk Influences | Incorporates elements of Purab ang (eastern dialects and melodies), making it linguistically and culturally rich. |

3. Pedagogical Philosophy and Methodology

The Banaras Gharana’s teaching tradition values emotional honesty, devotional immersion, and imaginative expression, alongside technical rigour.

Training Features:

Voice as Emotion Carrier

Students are taught to use the voice not just technically, but as a vehicle for feeling, often through bhajan or thumri.Deep Rasa Training

Much attention is given to understanding rasa theory, so that performances elicit genuine emotional responses.Intimate Compositions

Learning begins with compositions rich in poetic language, often invoking Krishna, Shiva, or Ganga, nurturing a personal connection.Rhythmic Sophistication

Despite its emotive nature, Banaras gayaki requires deep understanding of laya and tala, especially in semi-classical and tappa forms.Guru-Shishya Immersion

Students live with the guru in a shared spiritual-musical space, learning through absorption and lived experience.

4. Notable Exponents

The Banaras Gharana has produced some of India’s most cherished vocalists and semi-classical icons, particularly in thumri and devotional music.

Pandit Bhaiya Ganpatrao (19th century)

One of the foundational figures in developing the distinct thumri style of Banaras.Pandit Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit

A versatile exponent of both classical and semi-classical styles within the Banaras tradition.Siddheshwari Devi (1908–1977)

The legendary “Thumri Queen” of Banaras, renowned for her soul-stirring emotional expression and mastery of bhajans and dadras.Rasoolan Bai (1902–1974)

Celebrated for her earthy and bold thumris, deeply rooted in the Purab ang tradition of Banaras.Girija Devi (1929–2017)

Revered as the modern matriarch of Banaras gayaki, she brought thumri and semi-classical music to the national stage with unmatched dignity.Chhannulal Mishra

A contemporary maestro, known for his wide-ranging command over classical, semi-classical, and devotional repertoire.

5. Contemporary Relevance and Global Appeal

The Banaras Gharana has gained renewed attention for its emotional accessibility and cultural authenticity. It has become a bridge between classical rigor and folk vitality, attracting listeners from around the globe.

Featured in international festivals, recordings, and collaborations.

Gharana styles are taught in music universities, both in India and abroad.

Popular among audiences seeking a spiritual or aesthetic connection, beyond formal classical music.

The Banaras Gharana sings from the heart of India’s spiritual soul. With its melodic richness, emotional intensity, and devotional grace, it captures the essence of Varanasi—a place where sound becomes prayer, and music becomes an offering to the divine.

Dhrupad Gharanas – Ancient Lineages of Solemn Song

Dhrupad is the oldest surviving form of North Indian classical vocal music, revered for its meditative depth and rigorous discipline. Several distinct vani or styles (‘bans’) developed over the centuries. Here are the principal Dhrupad gharanas:

1. Dagarvani Gharana (Dagar Tradition)

Origins & Lineage

Traces back to the legendary Dagar family, said to descend from Tansen’s son. Flourished in Rajasthan and later in Gujarat under royal patronage.Stylistic Hallmarks

Meend‑rich alap on aakaar syllables (long, slow glides)

Profound emphasis on microtonal purity and sustained notes

Minimal rhythmic accompaniment in the alap, followed by solemn, measured nom-tom sections

Notable Exponents

Ustad Zahiruddin Dagar, Ustad Faiyazuddin Dagar, and their successors Ustad Kaivalya Kumar and Zia Fariduddin Dagar have kept this tradition alive internationally.

2. Darbhanga Gharana

Origins & Lineage

Flourished in the courts of Darbhanga (Bihar) under the patronage of the Maharajas. Linked to the Bettiah tradition but developed its own identity.Stylistic Hallmarks

Dramatic rhythmic interplay even in slow alap

Early introduction of bol-based improvisation (nom-tom)

Rich, ornate layakari (rhythmic play) once the alap gives way to the dagar

Notable Exponents

The late Pandit Ram Chatur Mallick and his family; more recently, Pandit Vidyadhar Vyas.

3. Bettiah Gharana

Origins & Lineage

Established in the Bettiah Raj (Bihar) by musicians brought from Delhi and Agra courts.Stylistic Hallmarks

Blend of refined lyricism and dhrupadic gravity

Use of textual clarity in dhrupad, with less extensive aakaar elaboration than Dagarvani

Moderate use of rhythmic improvisation

Notable Exponents

Pandit V. G. Jog has been a prominent 20th‑century ambassador of this style.

4. Kishangarh and Talvadi Variants

Origins & Lineage

Other regional strains—such as Kishangarh and Talvadi—arose in princely courts across Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.Stylistic Hallmarks

Courtly elegance (Kishangarh) or vigorous pulse (Talvadi) in *dhrupad

Distinct ornamentation and tonal colouring shaped by local aesthetics

Notable Exponents

These lineages survive today in small familial traditions and festival circuits.

5. Common Features of Dhrupad Gharanas

Despite regional differences, all Dhrupad gharanas share:

Four-part Structure

Alap (slow, unmetered exploration)

Jod/Jahal (introduction of pulse)

Nom‑tom (syllabic improvisation)

Bandish (fixed composition set to a specific tala)

Emphasis on Mantra‑like Repetition

Sustained, meditative chanting of syllables to reveal the raga’s essence.Minimal Accompaniment

Primarily pakhawaj (barrel drum) and tanpura, fostering a spacious aural canvas.Spiritual Orientation

Lyrics often drawn from Vaishnava or Shaiva bhakti poetry, reinforcing the devotional atmosphere.

The Dhrupad gharanas are living monuments to India’s musical antiquity, offering a portal into a contemplative, ritual-rooted sound world. Their austere beauty and disciplined frameworks continue to inform and inspire all subsequent schools of Hindustani vocal music.

The Instrumental Gharanas – The Senia Tradition of Sitar and Surbahar

The instrumental traditions of North Indian classical music are no less rich and diverse than their vocal counterparts. One of the most influential and renowned traditions is the Senia gharana, primarily associated with the sitar and surbahar. This tradition was founded by the legendary Tansen, whose influence permeates Hindustani classical music to this day. The Senia gharana is primarily associated with the sitar, but its influence extends to other instruments like the surbahar (a larger version of the sitar used for more meditative, slower renditions of ragas).

1. Senia Gharana – Roots and Lineage

Origins & Lineage

The Senia tradition is traditionally linked to Tansen, one of the navaratnas (nine jewels) in the court of Mughal Emperor Akbar. Tansen, considered the progenitor of Hindustani classical music as we know it, was a disciple of the renowned Dhrupad maestro Swami Haridas. His musical style, which emphasized intricate improvisation and ornamentation, was carried forward by his disciples, and became the foundation for the Senia gharana.The sitar, as an instrument, evolved under this lineage. While it was initially used in courts and royal settings, the Senia tradition is characterized by its association with the art of oral transmission and the deep spiritual nature of its compositions, much like the Dhrupad vocal tradition.

2. Stylistic Hallmarks of the Senia Gharana

Lyrical Phrasing

The hallmark of the Senia style is its deep connection to the human voice. The phrasing of the sitar and surbahar under this tradition mirrors the ornamentation and microtonal nuance of vocal Dhrupad music. Performers are trained to play with slow, deliberate tones, almost resembling a vocal alap in texture.Heavy Ornamentation (Meend)

Meend (sliding between notes) is central to the Senia style, reflecting the tradition’s vocal roots. It allows the musician to draw out the full emotional content of the raga, especially in slow compositions that require patient and sustained attention.Tabla Accompaniment

The sitar and surbahar are traditionally accompanied by the tabla, whose intricate rhythms complement the sitar’s slow and delicate phrasing. The rhythm of the tabla provides a framework but never dominates, allowing for the expansion and contraction of the raga’s melodic structure.Role of the Tanpura

Like in vocal music, the tanpura in instrumental performance serves as a grounding, providing the harmonic backdrop that supports the improvisational flights of the sitar. The consistent drone enhances the spiritual nature of the raga.

3. Notable Exponents of the Senia Gharana

Ustad Vilayat Khan

A legendary figure in the Senia tradition, Ustad Vilayat Khan is often credited with bringing the surbahar (a deeper, more meditative relative of the sitar) to prominence. His style emphasized not only technical mastery but also deep emotive playing that sought to capture the essence of the raga’s spiritual message. He was known for his ability to merge the intricate melodic ornamentation with a profound emotional resonance.Ustad Imrat Khan

Ustad Imrat Khan, the younger brother of Vilayat Khan, is another towering figure in the Senia gharana. He was one of the first to popularize the surbahar as a solo instrument. His mastery of improvisation and delicate phrasing has made him a respected figure in both Indian and international music circles.Ustad Rais Khan

Ustad Rais Khan, a leading figure in the Senia gharana, has played a pivotal role in both preserving and innovating within this tradition. His sitar playing is known for its elegance, sophisticated ornamentation, and ability to express the emotional depth of ragas.

4. Evolution of the Senia Tradition

Over time, the Senia gharana has undergone both evolution and preservation. While it continues to hold steadfast to the principles established by its forebears, it has adapted to the changing landscape of music in the modern era. The emphasis on spiritual connection, ornamentation, and emotional depth remains intact, but contemporary players like Anoushka Shankar and Nikhil Banerjee have infused the tradition with their unique interpretations, while still respecting its sacred heritage.

The Senia gharana has also fostered an atmosphere of innovation and exchange, with artists experimenting with new approaches to tuning, rhythmic structures, and the inclusion of Western instruments in the collaborative performances. This dynamic synthesis has helped preserve its relevance in a globalized world.

5. Common Features of the Senia Gharana

Slow, Patient Alap-like Introductions

Like in the vocal Dhrupad tradition, the instrumental performance often begins with a long and meditative alap, where the musician gradually unveils the mood of the raga, creating a deep and reflective atmosphere.Vocal-like Ornamentation

The ornamentation of the sitar in the Senia style closely mirrors the vocal tradition. The musician is trained to evoke the “voice” of the sitar, with every note imbued with emotion and subtle ornamentation.Emphasis on Emotional Expression

In keeping with Tansen’s legacy, emotional expression is paramount. The performer’s ability to convey the raga’s essence is considered more important than technical complexity. Expression of mood and a connection to the audience’s inner feelings are deeply valued.Fluid, Evolving Improvisation

Improvisation is at the core of Senia-style performances, with ragas unfolding naturally, evolving from simple phrases into complex and intricate expressions. The performer’s ability to navigate these variations and create an organic flow is a key measure of their mastery.

The Senia gharana, with its focus on the deep spiritual connection between sound and emotion, remains one of the most influential traditions in Hindustani classical music. From Tansen’s foundational contributions to the virtuosity of Vilayat Khan and his successors, the Senia tradition has ensured that the profound and meditative aspects of music continue to be explored and experienced by audiences around the world.

The Maihar Gharana – A Revolution in Indian Classical Instrumental Music

The Maihar Gharana is one of the most significant and innovative schools of Indian classical music, especially renowned for its contribution to sitar and sarod playing. Founded by the legendary Ustad Allauddin Khan, the gharana is known for its unique blend of traditional Hindustani classical techniques with innovative approaches that revolutionized the instrumental scene in the 20th century.

1. The Origins of the Maihar Gharana

Ustad Allauddin Khan’s Vision

The Maihar Gharana owes its foundation to Ustad Allauddin Khan, a towering figure in the world of Hindustani classical music. Born in 1862, he hailed from the small town of Maihar in Madhya Pradesh, which became the home of the gharana. Ustad Allauddin Khan was not only a master of sitar and sarod, but also a highly skilled musician on a variety of other instruments, including the surbahar and esraj. His expertise and eclectic approach led to the creation of a distinct style that fused various regional and classical traditions.Innovations in Playing Style

Ustad Allauddin Khan’s vision for the Maihar Gharana was not to follow existing traditions blindly, but to evolve and refine them. His style of playing was a fusion of intricate Raga development, elaborate improvisations, and intense technical mastery. His innovations included intricate ornamentations like meend, gamaka, and the use of tarab strings, which became a hallmark of his teaching and playing style.

2. Stylistic Features of the Maihar Gharana

Melodic Expression

Maihar Gharana’s instrumental performances are characterized by deep melodic expression, with the emphasis on both precision and emotional depth. The gharana prioritizes the vocalization of the raga, which means that every note is articulated with clarity and depth. The player is expected to imbue each note with a sense of feeling, ensuring that the raga communicates not just technically, but emotionally as well.Emphasis on “Alap”

The Alap, the slow introduction to a raga, plays a central role in the Maihar style. The way the raga unfolds in the hands of a Maihar gharana musician is deliberate, meditative, and deeply introspective. Ustad Allauddin Khan’s approach to the Alap has become one of the key stylistic features of the gharana, where the player takes time to slowly introduce each note and build the mood of the raga.Brevity and Precision in Taal

While the Maihar Gharana emphasizes emotional depth, it also maintains a high standard of precision, especially when it comes to rhythmic cycles (taals). Performers are trained to master complex rhythms and intricate taal structures, ensuring that while improvisation is encouraged, it always adheres to the rhythmic precision of the tradition.

3. Key Exponents of the Maihar Gharana

Ustad Ali Akbar Khan

The most famous disciple of Ustad Allauddin Khan was Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, who became one of the most prominent sarod players in the world. Ali Akbar Khan’s style carried forward the essence of the Maihar Gharana by emphasizing the fluidity of raga expression, innovative improvisations, and an emotional approach to playing. His interpretation of the sarod combined technical brilliance with deep musicality, which earned him worldwide recognition.Ustad Ravi Shankar

On the sitar, the Maihar Gharana was elevated by Ustad Ravi Shankar, who, although known for blending traditional Indian music with Western styles, maintained the foundational principles of Ustad Allauddin Khan’s teaching. Shankar’s performances are characterized by powerful emotive renderings of ragas, marked by precise and controlled improvisations. His collaborations with Western musicians, including his work with George Harrison of The Beatles, brought the Maihar style to global audiences.Ustad Amjad Ali Khan

The legacy of the Maihar Gharana has also been carried forward by Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, the son of the legendary sarod maestro Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan (a direct disciple of Ustad Allauddin Khan). Amjad Ali Khan’s playing is known for its sublime grace, immaculate control, and deep emotional expression, all of which are central tenets of the Maihar tradition. He has managed to stay true to his gharana’s essence while exploring new musical avenues.

4. The Role of Maihar Gharana in Shaping the Future of Indian Classical Music

The Maihar Gharana was instrumental in modernizing and popularizing instrumental classical music in India, particularly in the 20th century. The contributions of Ustad Allauddin Khan and his disciples helped bring Indian instrumental music to a broader audience, both within India and internationally. The gharana’s focus on blending tradition with innovation allowed it to remain relevant even as the music world evolved.

Sitar and Sarod – A Unique Symbiosis

One of the most significant contributions of the Maihar Gharana was its treatment of the sitar and sarod as parallel, yet distinct, instruments within Hindustani classical music. The gharana’s focus on deep emotional interpretation, along with technical mastery, allowed both instruments to evolve separately but in sync with each other. Today, the Maihar Gharana’s influence can be seen in many sitar and sarod players around the world.International Influence

The reach of the Maihar Gharana was further extended by Ustad Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, whose performances and collaborations with international artists introduced the gharana’s unique qualities to the West. Their work demonstrated the universality of Indian classical music, bridging cultures and spreading appreciation for the genre.

5. Common Characteristics of Maihar Gharana Performances

Expansive Alap

Like in other gharanas, the Alap in Maihar Gharana is expansive and slow, allowing the performer to build a connection with the listener, drawing them into the mood of the raga.Dynamic Creativity

Though rooted in tradition, Maihar performers are encouraged to experiment with the raga’s melodic structure, introducing novel variations and improvisations. This creativity is balanced with rigorous adherence to the ragas’ emotional essence.Rhythmic Control

Maihar Gharana practitioners possess an extraordinary command over rhythm, with a focus on complex rhythmic structures that enhance the melodic flow. Precision in executing rhythmic cycles is a hallmark of this gharana.

The Maihar Gharana represents a unique blend of innovation, creativity, and traditional virtuosity. The legacy of Ustad Allauddin Khan continues to inspire and shape the world of Hindustani classical music, ensuring that his contributions to the sitar, sarod, and overall instrumental music continue to resonate for generations to come. With its ability to marry the deep spirituality of Indian classical music with dynamic improvisations, the Maihar Gharana stands as one of the most influential musical traditions in India’s rich heritage.

Banaras (Benares) Gharana (Instrument) – The Rhythmic Heartbeat of Hindustani Music

1. Historical Origins

The Banaras Gharana, often spelled Benares Gharana, is predominantly celebrated today as a tabla tradition, though it also encompasses distinctive vocal and instrumental styles within the sacred city of Varanasi (Banaras). Its roots extend into the 19th century, when Varanasi’s status as a spiritual and cultural epicentre nurtured numerous musicians and dancers.

In the world of percussion, the Banaras Gharana was founded by Pandit Ram Sahai (circa 1810–1900), who is credited with codifying many of its characteristic compositions (peshkar, kaida, rela, gat, and chakradhar). His innovations laid the groundwork for a tradition that combined vigorous strokes with lyrical melodies on the tabla.

2. Stylistic Characteristics

The Banaras Gharana of tabla is distinguished by its powerful sound, wide tonal palette, and inventive rhythmic compositions:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Open, Resonant Strokes | Emphasis on Na, Ge, and Tin strokes delivered with a full, ringing tone that carries well in both solo and ensemble settings. |

| Lyrical Compositions | Peshkars and gats feature melodic patterns that mirror raga motifs, blending rhythm and melody in a uniquely Banaras idiom. |

| Complex Kaidas | Inventive kaidas (theme-and-variation pieces) that explore permutations of basic bols, challenging both player and listener. |

| Relas and Chakradhars | Fast-paced relas (flourishes) and structured chakradhars (cyclic compositions) showcasing virtuosity and mathematical precision. |

| Integration with Dance | Close association with Kathak dance of Banaras, leading to tabla accompaniments that intimately reflect and support rhythmic footwork. |

These characteristics combine to create a style that is both robust and refined, capable of both thunderous excitement and subtle elegance.

3. Pedagogical Tradition

Teaching in the Banaras Gharana follows the guru–shishya paramparā, with a focus on oral transmission, daily practice, and performance etiquette. Key elements include:

Bols and Basic Compositions

Students first master the fundamental bols (tabla syllables) and simple kaidas before advancing to more elaborate pieces.Voice Imitation

The teacher often sings compositions aloud, and the pupil must echo them precisely on the tabla, fostering acute aural memory.Fingering and Stroke Techniques

Detailed instruction in hand positions and stroke mechanics ensures consistent clarity of tone.Repertoire Building

Gradual learning of peshkars, kaidas, gats, relas, and chakradhars, often culminating in extensive improvisational solos.Accompaniment Skills

Pupils learn to accompany vocalists, instrumentalists, and dancers, understanding the nuances of layakari (rhythmic interplay) in different contexts.

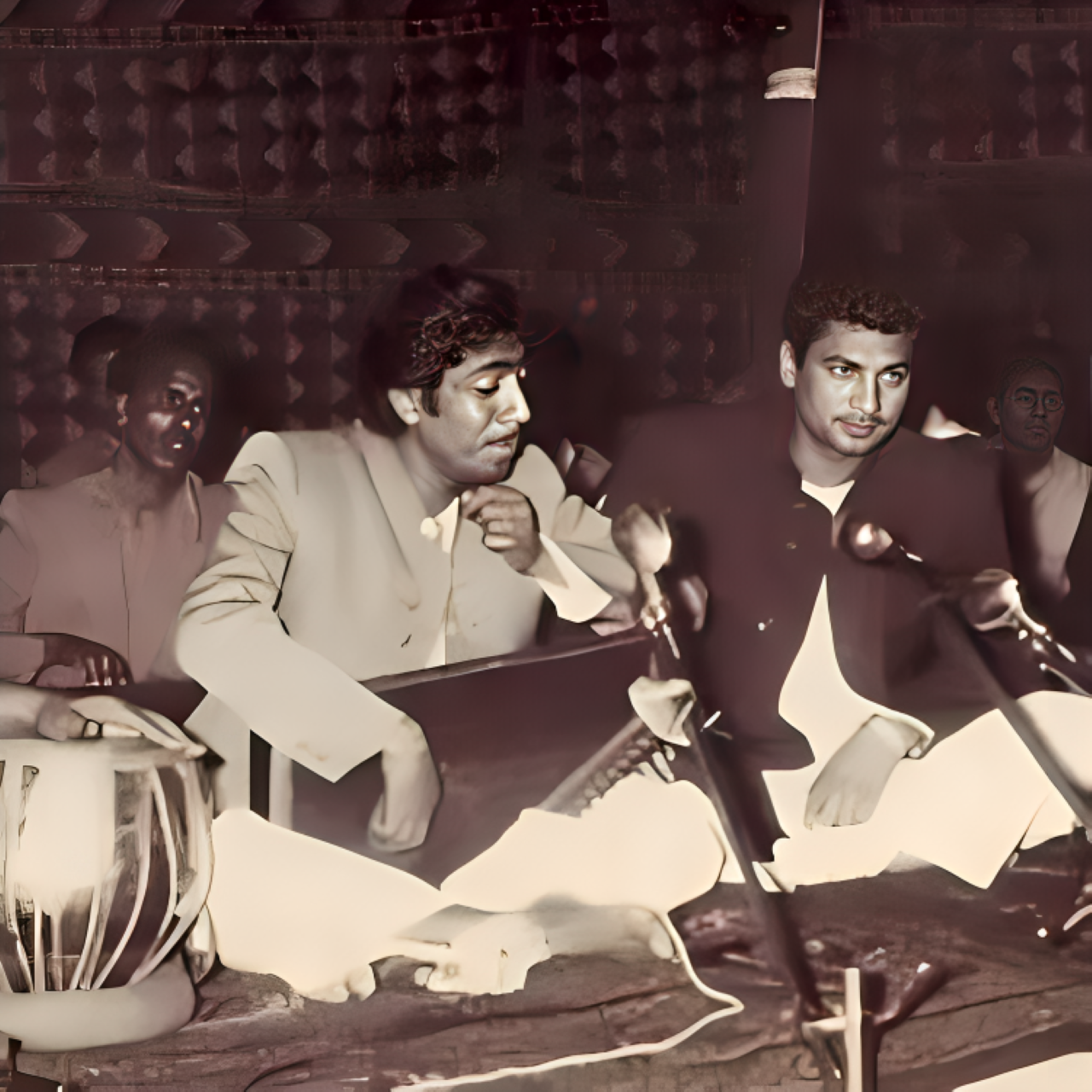

4. Eminent Exponents

Over two centuries, the Banaras Gharana has produced an illustrious roster of tabla maestros:

Pandit Ram Sahai (1810–1900)

Founder of the gharana, who formalised its core repertoire and stroke techniques.Pandit Anokhelal Mishra (1914–1949)

Renowned for his clarity, power, and musicality, he shaped the modern Banaras sound.Pandit Kishan Maharaj (1923–2008)

A dynamic performer whose solo recitals and Kathak accompaniment brought international acclaim.Pandit Samta Prasad ‘Bachaa Sahib’ (1921–2009)

Celebrated for his virtuosic flair and lyrical accompaniment, he bridged classical rigor with popular appeal.Pandit Anindo Chatterjee (b. 1954)

A living legend whose innovative solos and collaborations continue to expand the gharana’s horizons.Pandit Suresh Talwalkar (b. 1948)

Known for his philological approach and rhythmic sophistication, he is both a performer and a scholar-teacher.

5. Legacy and Contemporary Influence

The Banaras Gharana remains a vibrant force in classical music and dance today:

Tabla Solo Concerts: Its solo repertoire is a staple at festivals worldwide, demonstrating the gharana’s exuberant repertoire and virtuosity.

Collaborations: Banaras tabla players are highly sought after by Kathak dancers, classical musicians, and fusion ensembles, reflecting the gharana’s versatility.

Teaching and Scholarship: Institutions and private gurus continue the tradition, ensuring that the gharana’s oral repertoire is preserved and disseminated.

Innovation: Modern exponents experiment with new talas, compositions, and cross-cultural projects, keeping the tradition dynamic and relevant.

The Banaras Gharana epitomises the rhythmic soul of Hindustani classical music. With its blend of robust strokes, lyrical compositions, and dance intimacy, it has shaped the art of tabla playing for generations. Its exponents continue to inspire, innovate, and enthral audiences, ensuring that the Banaras beat remains an enduring heartbeat of Indian music.

A Symphony of Gharanas – The Vibrant Tapestry of Hindustani Music

As we draw to a close on this exploration of the diverse and rich Gharanas of Hindustani classical music, it becomes clear that each gharana is not just a school of thought, but a living, breathing expression of tradition, innovation, and cultural identity. From the maestros of Gwalior and Agra to the profound rhythms of Banaras, every gharana represents a unique approach to music that has shaped the history and evolution of Hindustani classical performance.

The Gharana system remains a cornerstone of Indian classical music, blending pedagogical structure, emotional depth, and virtuosic skill to craft a music that is not just heard, but felt in the soul. Each gharana, with its distinctive characteristics and artistry, contributes to a broader musical ecosystem, nurturing a tradition that has endured for centuries and continues to evolve.

Key Takeaways:

Cultural Significance: Each gharana is tied to a specific geographic region or cultural milieu, giving it a distinct sound and aesthetic that reflects the rich history and lifestyle of its origin.

Artistic Diversity: The gharanas embody a broad spectrum of musical styles, from the deeply meditative compositions of the Dhrupad tradition to the lighter, more improvisational tones of the Khyal style.

Transmission of Knowledge: The guru-shishya tradition remains the backbone of Indian classical music, where learning is an immersive and ongoing process. This system ensures the continuity and preservation of the gharana’s unique legacy.

Innovative Contributions: While rooted in tradition, many gharanas have evolved through the contributions of innovative musicians, infusing contemporary and experimental elements into their performances and compositions.

Global Influence: The reach of Hindustani classical music, with its gharanas at the forefront, continues to extend far beyond India’s borders, influencing musicians and composers worldwide, and finding relevance in modern fusion genres and global music festivals.

The intricate beauty and vast variety of Hindustani classical music would not be what it is today without the Gharanas. They are the living repositories of knowledge, discipline, and artistry, and through their continued evolution, they ensure that the vibrancy of Indian classical music will continue to resonate with listeners and musicians alike for generations to come. Whether through the tabla’s rhythmic heartbeats in Banaras or the graceful melodies of Gwalior, the Gharanas are the heartbeat of this timeless tradition, reminding us that music is a journey that transcends boundaries.

As we reflect upon the invaluable contributions of these traditions, we celebrate the richness, diversity, and universality of Hindustani classical music. In its ever-evolving journey, the Gharanas serve as both keepers of history and harbingers of the future, ensuring that the soul of Indian classical music continues to inspire and captivate the world.

References:

Maqbool, A. (2003). The Gharana System in Hindustani Classical Music. Delhi: Sangeet Academy Press.

Kauffman, A. (2011). A Historical Overview of the Hindustani Music Gharanas. New York: Musicology Publications.

Sharma, S. (2017). Gharanas and their Influence on Indian Classical Music. New Delhi: Indian Classical Music Society.

Bharati, N. (2010). The Music of India: Hindustani Classical Music. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Verma, M. (2015). The Tradition of Khayal and Its Gharanas. Varanasi: Benares Music Institute.

Jha, R. (2005). Agra Gharana: The Unbroken Tradition. Mumbai: Hindustani Music Archives.

Pandit, A. (2012). Vocal Styles of Hindustani Classical Music: An Insight into the Gharanas. Pune: Sangeet Prakashan.

Nayak, R. (2014). Tabla Gharanas and Rhythmic Tradition in Hindustani Music. Kolkata: Rhythmic Arts Publishers.