Salil Chowdhury (Hindi: सलिल चौधरी, Malayalam: സലിൽ ചൗധരി), affectionately known as Salilda, was born on 19 November 1925 in Ghazipur, in the South 24 Parganas district of what was then Bengal Presidency, British India (now West Bengal, India). He was the second of eight children in a Hindu Kayastha family. His father, Dr Gyanendramoy Chowdhury, served as a physician at the Latabari tea gardens in Assam, where young Salil spent much of his childhood surrounded by the everyday music of the garden workers and their spontaneous cultural performances.

Primary Musical Exposure

Salil’s first lessons came from his father’s own collection of Western classical records and from his cousin Nikhil Chowdhury, whose ensemble Milon Parishad introduced him to a multitude of instruments—flute, piano, violin, esraj—and the concept of blending Indian folk with global sounds salilda.com.Formal Schooling

He completed his matriculation and Intermediate Science (I S C.) from Harinavi School in Subhashgram, South 24 Parganas, in first class, then went on to earn a B.A. from Bangabasi College, Calcutta, graduating in the mid-1940s.

Key Takeaways – Early Years

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Birth | 19 Nov 1925, Ghazipur, 24 Parganas, Bengal Presidency |

| Family Background | Second of eight; father a tea-garden doctor; childhood in Assam tea gardens |

| First Musical Influences | Western classical records at home; cousin’s Milon Parishad ensemble |

| Education | Harinavi School (Matric & I SC 1st Class); B.A., Bangabasi College, Calcutta |

Table of Contents

Entry into IPTA and the Birth of Revolutionary Songs

In 1944, while pursuing his MA in Calcutta, Salil Chowdhury joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA)—the cultural arm of the Communist Party of India. This marked the beginning of his public musical career and his lifelong commitment to marrying art with social activism.

The Political and Cultural Milieu

Bengal Famine (1943–44): Salil witnessed the human tragedy of over two million deaths from starvation and disease. This experience infused his music with empathy for the oppressed and sharpened his political consciousness.

Indian National Army (INA) Trials (1945): The return of freedom fighters from Andaman jails inspired Salil’s early compositions, which gave voice to popular sentiment against colonial injustice.

Iconic IPTA Anthems

Salil’s first songs were tailored for IPTA’s touring theatre troupe, bringing folk‐inspired, multilingual music to towns and villages. They combined rural motifs, vocal harmonies, and poignant lyrics, quickly becoming staples of the freedom movement.

| Song Title | Year | Theme / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| “Becharpoti Tomar Bichar” | 1945 | Call for justice; set to a kirtan melody during INA trials |

| “Uru Taka Taka Taghina Taghina” | 1944–45 | Harvest and sowing; early folk‐rhythmic experiment with multi‐layer vocal harmonies |

| “Aalor Desh Theke Andhar Paar Hoyee” | 1945–46 | Hope and resilience amid famine; layered choral arrangements |

| “Kono Ek Gayer Bodhu” | 1943–46 | “Village Bride”—a rural love song turned allegory for rebirth in post‐famine Bengal |

| “Runner” | 1945 | Poetic celebration of working‐class struggle; set to Sukanta Bhattacharya’s poem |

| “Abak Prithibi” | Mid-1940s | Reflection on a world turned upside‐down by war and colonialism |

These anthems were rendered by leading voices of the era—Hemant Kumar, Shyamal Mitra, Manabendra Mukherjee, Pratima Bandyopadhyay—and cemented Salil’s reputation as a composer who could articulate the aspirations of “the common man”.

Musical Innovations

Fusion of Western and Folk Elements: Salil adapted Western orchestral techniques—counterpoint, harmonic layering—into simple folk tunes, creating a global yet grassroots sound.

Vocal Polyphony: Through his later founding of the Bombay Youth Choir (1958), Salil perfected multi‐voice arrangements first trialled in these IPTA songs.

Storytelling through Song: Each composition narrated a mini‐drama of social struggle or hope, foreshadowing his later work as a lyricist and filmmaker.

From Stage to Screen – The Bengali Film Era (1949–1953)

Following his success with IPTA, Salil Chowdhury made a seamless transition to cinema. His deep understanding of narrative music and folk sensibilities proved ideal for the silver screen’s evolving demands in post-independence Bengal.

1. Debut with Parivartan (1949)

Film: Parivartan

Year: 1949

Director: Niren Lahiri

Highlights:

Salil’s first film score, blending IPTA-inspired choruses with Bengali folk tunes.

Songs such as “Tumi Ke Hawar” and “Moner Bane” established him as a composer capable of evoking both rural colour and urban emotion.

2. **Establishing a Bengali Catalogue (1949–1952)

Salil scored over a dozen Bengali films within four years, crafting music that departed from the prevalent theatrical style and embraced naturalistic soundscapes:

| Film | Year | Notable Songs | Style & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parivartan | 1949 | “Tumi Ke Hawar,” “Moner Bane” | Fusion of folk chorus and Western harmony |

| Nirjan Saikate | 1950 | “Tora Sundor” | Lush orchestration symbolising monsoon romance |

| Baje Bhajna | 1951 | “Pagla Hawa” | Rustic percussion, rustic lyrics |

| Bicharak | 1952 | “Akashe Phool Phote” | Lyrical melody reflecting rural pathos |

| Sagarika | 1952 | “Dure Jaio Na” | Semi-classical alap introduction |

Each score showcased Salil’s gift for melodic economy—a single theme would reappear, varied through instrumentation or tempo to mirror on-screen moods.

3. Innovations in Bengali Film Music

Orchestration:

Salil introduced string quartets, flute interludes, and light percussion (tabla, dhol) into Bengali scores, moving away from piano-only accompaniments.Leitmotif Technique:

He pioneered the use of leitmotifs (recurring musical phrases tied to characters or ideas), a method borrowed from Western opera.Poetic Lyrics:

Collaborating with poets like Bani Thakur and Premendra Mitra, Salil elevated song texts to standalone poetry.

4. Critical Reception and Legacy

By 1952, critics were hailing Salil Chowdhury as the “Modern Minstrel of Bengal”. Publications like Ananda Bazar Patrika praised his ability to “capture Bengal’s soul in three minutes”. His Bengali scores remain staples on radio and in cultural programmes, influencing subsequent generations of composers.

The Golden Era of Hindi Cinema – Salil Chowdhury’s National Appeal (1953–1960)

The early 1950s marked the beginning of Salil Chowdhury’s expansion beyond Bengali cinema into Hindi films. His entry into this broader, pan-Indian cinema world was not only a step toward national recognition but also a phase that solidified his reputation as a versatile and deeply innovative composer.

1. Debut in Hindi Cinema: Do Bigha Zamin (1953)

Film: Do Bigha Zamin

Year: 1953

Director: Bimal Roy

Highlights:

Salil’s score for Do Bigha Zamin is considered a watershed moment in Indian cinema. The film’s stark, realist portrayal of rural poverty demanded a musical score that could enhance its grim realism while maintaining an emotional core.

The song “Babu Moshai Zindagi Badi Haseen Hai” became iconic for its poignant melody and its deep philosophical lyrics by Shailendra. The music was sparse, almost minimalist, with Salil employing simple yet evocative orchestration.

The film’s score exemplified Salil’s ability to match melody with narrative, using evocative music that captured the emotional turmoil of the characters while subtly underscoring the socio-political themes of the story.

2. Exploring Folk and Classical Fusion (1954–1957)

Following the success of Do Bigha Zamin, Salil Chowdhury’s unique blend of Indian folk traditions with Western classical structures began to define his Hindi film scores. His understanding of Western harmony combined with Indian classical ragas created a sound that was rich and layered, yet deeply grounded in the Indian tradition.

| Film | Year | Notable Songs | Style & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parakh | 1954 | “Yeh Raat Bheegi Bheegi” | Fusion of Hindustani classical and jazz-like rhythm |

| Shree 420 | 1955 | “Mera Joota Hai Japani” | Incorporation of Western pop and jazz elements |

| Nau Do Gyarah | 1957 | “Aaja Aaja Main Teri Galiyon Mein” | Folk-based rhythms infused with cinematic operatic style |

The song “Aaja Aaja Main Teri Galiyon Mein” from Nau Do Gyarah (1957) is one of the most famous examples of Salil’s use of western jazz alongside Indian folk music, showcasing his dexterity in blending seemingly contrasting genres seamlessly.

3. Innovations in Orchestration: The Voice of the Orchestra

Salil Chowdhury’s innovation extended beyond melody and lyrics. His orchestration was unlike anything heard in Bollywood until then. He brought in full orchestras, strings, and brass sections to Indian cinema scores, all carefully orchestrated to create a cinematic experience rather than just a background score.

Use of Strings:

His strings, particularly the violins, were used to build tension, emotion, and drama, a technique he had mastered in his Bengali work.Use of Western Instruments:

While many Indian composers were relying heavily on Indian instruments, Salil experimented with piano, saxophone, and accordion, creating unique textures in his music.Emotional Underpinning:

Salil’s orchestration wasn’t just about complexity; it was about emotional restraint and subtlety, with music that emphasized the inner turmoil or hope of the characters.

4. Salil’s Influence on Film Music and Popular Culture (1957–1960)

By the end of the 1950s, Salil Chowdhury was being hailed as one of Bollywood’s greatest music composers, having established a sound that was distinctly his own. Unlike other composers of the time, he avoided the overused tropes of grand orchestras or typical playback singer performances. He preferred simpler, more intimate compositions, which was a refreshing contrast to the extravagance of other contemporary scores.

A Song for the Masses:

His work resonated with the common man; songs like “Mera Joota Hai Japani” from Shree 420 (1955) became anthems of independence and modernity.Subtlety and Depth:

Even in his more melancholic songs, such as “Zindagi Kaisi Hai Paheli” from Anari (1959), Salil’s understated style made each note significant, drawing the listener into the emotional core of the character.

5. Legacy and Recognition: A National Presence

By the end of the 1950s, Salil Chowdhury was no longer just a regional composer. He was a national figure whose work spanned both Bengali and Hindi films, influencing the very soul of Indian cinema music. His ability to fuse folk, classical, and Western elements into a cohesive sound was unparalleled, and his focus on simplicity and emotional depth gave his music a timeless quality.

Expanding Horizons — Bombay Youth Choir, Malayalam Cinema, and Social Commitment (1958–1975)

By the late 1950s, Salil Chowdhury had firmly established himself in both Bengali and Hindi cinema. Yet his restless creativity spurred him to explore new frontiers—founding India’s first secular choir, composing for Malayalam films, and using music as a force for social change.

1. The Bombay Youth Choir (1958)

In 1958, Salil founded the Bombay Youth Choir, India’s first secular vocal ensemble dedicated to polyphonic arrangements of Indian folk and contemporary songs. Under his baton, young singers learned multi-voice harmonies, counterpoint, and the union of East–West musical idioms.

Mission: Democratise choral singing by embracing India’s diverse languages and traditions.

Repertoire: Folk tunes from Bengal, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Kerala; adapted with Western harmonic structures.

Impact: Inspired a nationwide choral movement—today, many city choirs trace their origins to Salil’s pioneering work.

2. Foray into Malayalam Cinema (1964–1975)

Salil’s Malayalam film debut came with Chemmeen (1964), directed by Ramu Kariat. Though the film’s score was composed by Salil, the production’s majesty propelled the songs to instant popularity across South India.

| Film | Year | Notable Songs | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemmeen | 1964 | “Rajahamsame” | A haunting melody blending Carnatic motifs with Western strings. |

| Ithu Njangalude Katha | 1970 | “Madhura Swapnangal” | Dreamy, semi-classical composition for Kamal Haasan’s debut. |

| Raasaleela | 1975 | “Anuraga Ganam Pole” | Lyrical, romantic ode with folk undertones. |

Across 26 Malayalam films, Salil adapted his style to local tastes—employing Carnatic ragas, Kerala’s folk rhythms, and his trademark Western harmonies. His scores remain staples of Malayalam radio and stage.

3. Socially Committed Music

Salil Chowdhury never lost his activist roots. During Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971, he composed “Bangla Amar Bangla” and other anthems for the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, the clandestine radio service of the Mukti Bahini.

Lyrics & Themes: Geared toward freedom, unity, and resistance—echoing his IPTA days.

Posthumous Honour: In 2012, the Government of Bangladesh awarded him the Muktijoddha Maitreye Samman for his invaluable contributions to the liberation struggle.

4. Parallel Cinema and Filmmaking

In 1966, Salil wrote, directed, and composed for Pinjre Ke Panchhi, starring Meena Kumari and Balraj Sahni. Though the film received mixed reviews, it showcased Salil’s skills as a storyteller and his willingness to experiment beyond pure music.

He also collaborated with Mrinal Sen on Bhuvan Shome (1969), widely regarded as the pioneer of New Indian Cinema, scoring its subtle, satirical tone with restrained yet evocative music that underscored Sen’s modernist vision.

5. Literary Pursuits: Poetry and Prose

Beyond films and theatre, Salil was an accomplished poet and short-story writer. His published collections include:

Kobita (Poems)

Prantorer Gaan (Songs of the Borderlands)

Salil Chowdhurir Gaan (1983)

These works reveal his social conscience, lyrical finesse, and enduring belief in music’s power to reflect and reform society.

Salil Chowdhury’s mid-career years cemented his reputation as both an innovator and a humanitarian artist—a composer willing to cross linguistic and regional boundaries, to found new musical institutions, and to lend his voice to the most pressing social causes of his time.

The Final Decades (1976–1995) – Awards, Later Works, and Legacy

In the last two decades of his life, Salil Chowdhury continued to compose for films across multiple languages, pursue literary projects, and receive numerous honours recognising his unparalleled contribution to Indian music and culture.

1. Late Filmography and Genre Diversity

Between 1976 and 1994, Salil’s musical output spanned Hindi, Bengali, Malayalam, Marathi, and several regional cinemas. Though fewer in number than his earlier decades, these scores exhibit his trademark fusion of folk, classical, and Western elements:

Hindi Highlights

Kyun! Kabhie Kabhie (1976): Poignant orchestral theme underlining generational drama.

Mrigayaa (1977): Haunting tribal rhythms reflecting rural unrest.

Jeevan Jyoti (1976): Melodic ballads rooted in folk traditions.

Swami Vivekananda (1994): A devout, meditative score for G. V. Iyer’s spiritual biopic.

Malayalam & Regional

Bashu, The Little Stranger (1989, Bengali): An evocative score for a refugee’s odyssey.

Samanmayam (1978, Malayalam): Lyrical melodies weaving through family drama.

2. Major Awards and Recognitions

| Year | Award & Institution | Work / Reason |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Filmfare Award for Best Music Director | Madhumati (Most Filmfare wins, including Best Music) |

| 1966 | Uttar Pradesh Film Patrakar Sangh Puraskar | For direction of Pinjre Ke Panchhi |

| 1973 | Bengal Film Journalists’ Association Award | Lifetime achievement in Bengali cinema |

| 1985 | Allauddin Smriti Puraskar (West Bengal Government) | Outstanding contribution to Bengali music |

| 1988 | Sangeet Natak Akademi Award | National honour for excellence in music composition |

| 1990 | Maharashtra Gaurav Puraskar | Recognition by the state of Maharashtra |

| 2012 | Muktijoddha Maitreyi Samman (Government of Bangladesh) | Posthumous honour for contributions during the Liberation War |

Salil’s Filmfare Award in 1958 for Madhumati was particularly significant: it acknowledged his elevating of film music to an art form that could express deep emotion through innovative orchestration, blending Indian melodies with Western counterpoint.

3. Literary and Cultural Contributions

Even as his film work slowed, Salil remained active in:

Poetry Collections:

Kobita (Poems)

Prantorer Gaan (Songs of the Borders)

Essays and Short Stories: Published in Bengali and Hindi journals throughout the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting on music, social change, and personal memoir.

He also continued to conduct the Bombay Youth Choir until the early 1990s, mentoring a new generation of singers in polyphonic and cross-cultural repertoire.

4. Final Years and Passing

Salil Chowdhury’s health declined in the early 1990s. Despite illness, he completed the score for Swami Vivekananda (1994)—a fitting capstone to a career blending spiritual depth with musical craftsmanship.

He passed away peacefully on 5 September 1995, leaving behind an oeuvre of more than 75 Hindi, 41 Bengali, 26 Malayalam, and numerous other regional films, along with a rich legacy of songs, poems, and institutional innovations.

5. Enduring Legacy

Salil Chowdhury’s work continues to resonate:

Revival Performances: Bombay Youth Choir’s annual concerts include his choral arrangements.

Radio and Streaming: His film songs are routinely featured on All India Radio retrospectives and modern streaming playlists.

Scholarly Studies: Musicologists cite Salil’s fusion techniques in papers on Indo–Western cross-pollination.

Documentaries: Biographical films and TV specials in Bengal and Mumbai revisit his life, featuring interviews with contemporaries like Hemant Kumar and Pandit Hridaynath Mangeshkar.

Salil Chowdhury remains revered as a “composer of the masses and the classes”—an artist whose melodies bridged social divides and whose innovations enriched India’s musical tapestry for generations to come.

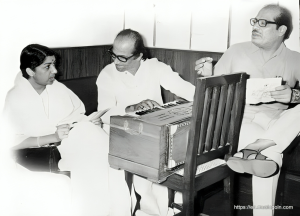

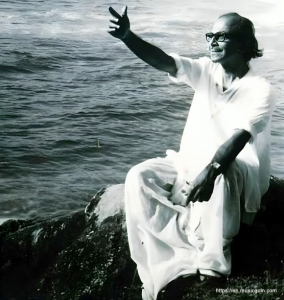

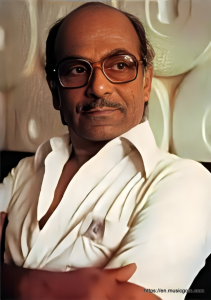

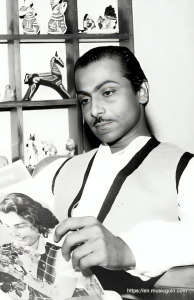

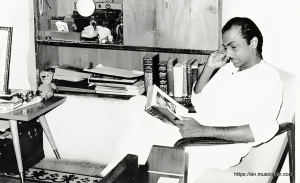

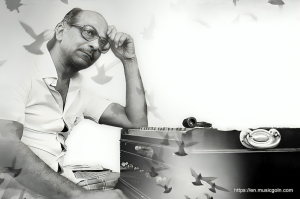

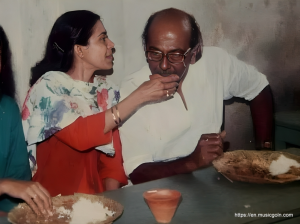

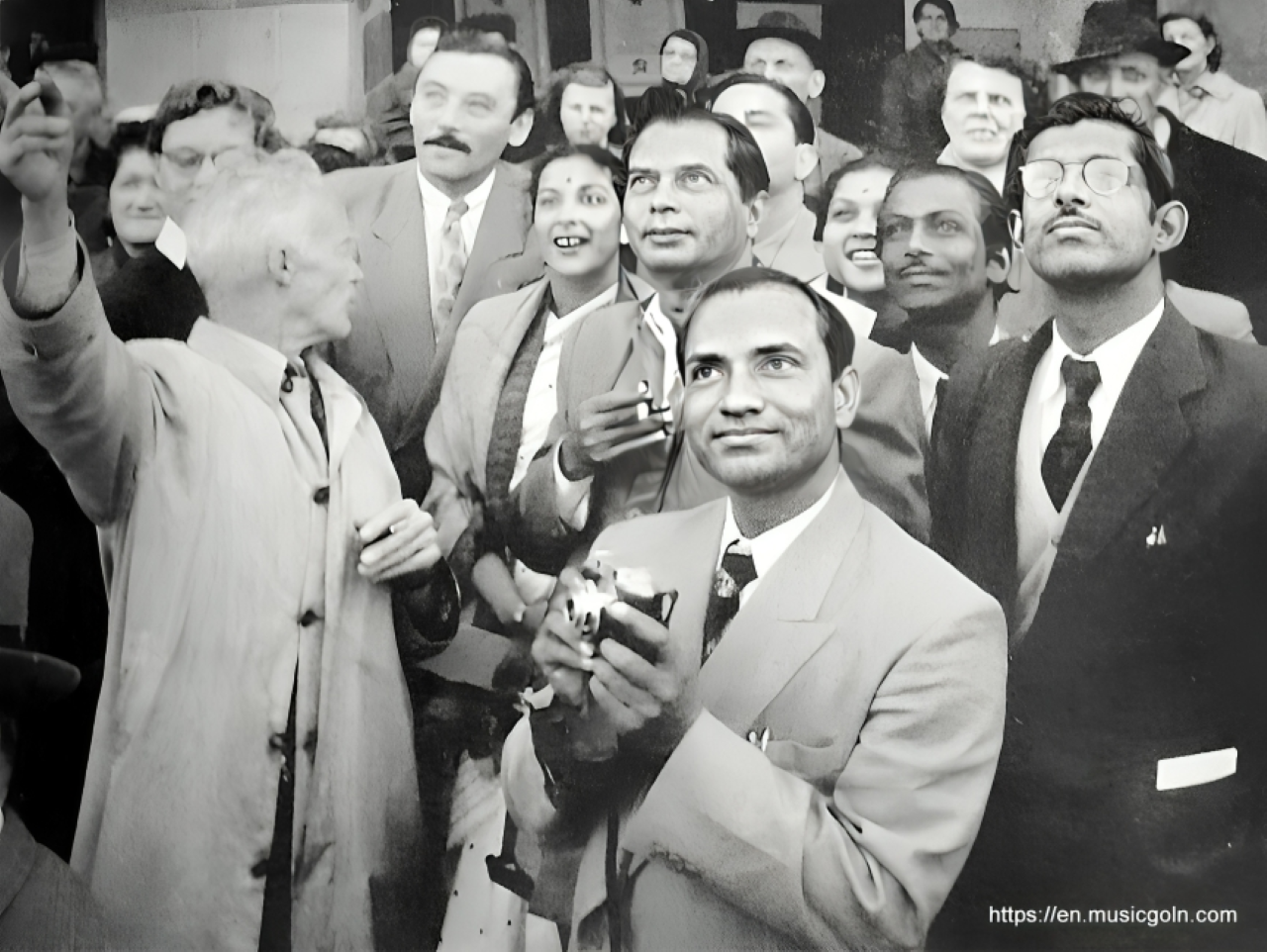

Photos: